Howdy! I’m a volunteer soccer coach in AYSO’s Region 13, in Pasadena CA. All fall, you’ll find me coaching my 3 kids’ soccer teams. After having done this for a few years, here’s what I think you can do to coach a winning recreational soccer team.

If you make player development your top priority, your team will get better, faster, than the coaches who dont. The kids are doing their best, but are limited by cognitive and emotional obstacles. As coaches, we can try to understand each child’s unique situation and provide them with pathways through or around those obstacles.

I grew up in Seattle, where everyone plays soccer. Seattle has a strong enough program to have neighborhood leagues where kids can be on a team with their neighbors, which builds strong friendships. I even played through middle school as sweeper on the travel team (the B team, that is), and coached and refereed for the pee-wee program at the community center. My refereeing was not great, but the parents were encouraging anyway. Attempts to teach the 4-year-olds about tactics, however, resulted in total disaster. Eventually, I learned to just tell the kids to run and kick the ball, and everyone had a good time.

So, fast-forward to being a parent, and I volunteered to referee for my oldest child’s 6U team. Count the kids on the team, count the number of jobs, and I figured someone has to do it. Fortunately, we got lucky with an excellent coach that year, and the Green Army Hawk Kickers had a lot of fun together. Except one kid. He never wanted to practice with the other kids, and sat on the sidelines, all dressed up in his uniform, for the games. So there I was, running laps or sitting and watching my son’s practice, and there’s this boy being miserable and alone. What could I do? I grabbed a ball and asked him if he would play pass with me. He never stepped on the field, but at least he learned how to kick and dribble with both feet.

Then, one week, our coach was injured in a non-soccer-related accident, and the assistant coach asked me to help with practice. A field promotion! As the referee, you have the best view, and I’d noticed that the GAHK were good at scoring, but their set pieces were weak, and I could tell that the kids were frustrated about losing possession so often. So we practiced kickoffs, throw-ins, and goal kicks, doing them over and over again until everyone knew where to go. It felt great!

That’s what coaching youth sports is all about: you make connections with people, you watch them play, and you try to show a way forward.

Those boys are still the same age as mine, so every time we see them around town, I get to reconnect with their parents while the kids exchange stories of their latest exploits. That’s the other thing you get from recreational sports — a community that endures for years and years.

Now I coach all three of my kids’ soccer teams, because what else is life for? They’re only young once.

Among team sports, soccer is the easiest for beginners. Do you want your kids to have a chance to struggle through and overcome challenges? To be proud of themselves for working hard to improve? To practice working with a team?To experience losing? Then give soccer a try.

OK, so your spouse voluntold you to coach of your kid’s soccer team. You might be thinking anything from “but I don’t know anything about soccer” to “dude, hold my beer.”

The first thing to know is that it’s not the same as coaching a competitive team. A recreational league is when you have a pool of kids, and a pool of volunteer coaches. Every year, you shuffle the kids and the coaches around, so today’s opponents might be next year’s teammates. And that referee who keeps making terrible calls just might be your kid’s coach next year.

If the league organizers did a good job, you’ll lose half your games. Half the kids you’re coaching are below average. Actually, more than half, because the best players are driving all over the state in a fancy club team. So, for your team, success isn’t winning, it’s helping everyone (including the referees) to have fun so they return next year.

That gets us to the second thing. You might think that soccer is a contest between the players. But, no. It’s a mathematical game played among the coaches. Consider that every coach gets a representative sample of normal, kids. Some are agile, some are clumsy. Some are quick, some are slow. Well, since they don’t have PE in schools anymore, most are clumsy and slow. It’s fair because everyone is starting from behind, and you and all the other coaches get the same hour per week to practice with your team. What you choose to do in that hour makes the difference between winning half your games and winning most of your games.

The first thing you want to do is get the parents together for a team meeting. A team comes with 8–10 families. It needs 2 coaches, 2 referees, and 1 manager. You can smirk knowingly when you point this out to the parents, because they’ll be conspicuously avoiding eye contact. The key is to remain silent while they used to the idea of being a role model for their own kids, and then a few parents are bound to agree to become your assistant coach, referees, and manager.

The most important idea to convey to new soccer parents is that 5-year-olds playing soccer is not actually a big deal. Toddlers have a way of demanding their parents’ attention away from the big picture. It’s hard enough for a kid to focus on the game without her parents running back and forth, yelling for her attention. Team sports are new and exciting, so for 5-year-olds, the whole extended family comes to watch and cheer. By the time they’re 14, their parents may slow the car to a crawl to drop them off at the game. So, if you’re starting with young players, encourage parents to direct their enthusiasm into being consistently positive and supportive. Especially toward that first-time referee, who is bravely muttering “fake it until you make it” under her breath.

Around about week two, you’ll start to wonder whether the parents think of you simply as cheap daycare. Nip that in the bud. It's good practice to send a weekly email, highlighting what you saw that you liked (so they know you're paying attention) and describing what you'll be working on (so they don't send an angry email complaining that you're not helping their player develop). If you also use this to thank the parents who stayed to monitor the commotion and retrieve balls, at least those parents will keep coming back.

Hardly a season has gone by when some parent hasn't made things worse for one of my players by making her drill on something that is actually counterproductive. For instance, if a player tends to stand still and kick the ball, the parent will have her take shots on goal, thus reinforcing the standing-still behavior. Or if what I really want the kid to do look around and be aware of her surroundings, the parent will encourage doing a lot of dribbling while looking down. You'll know this has happened when the parent approaches you at practice, proudly seeking approval. You could tell the parent what you really think ("Please don't try to coach your children!") or, if you're better coach than I, say something Positive, Instructional, and Encouraging.

What happens when Alice kicks at where the ball used to be? We want her parents to smile and cheer, “Yay! Go, Alice!” I think that overprotective behavior stems from fear, and fear is rooted in uncertainty. To help the parents feel more comfortable, and to think of you as an authority figure, tell parents about what you observe in their kids, what the next stage is, and what you’re doing to get them there. In the absence of having a development plan for each player (more on that later), try saying one of these:

Soccer isn’t just a game. It’s war. To be precise, Land War In Europe. The Europeans have been going at each other for thousands of years, and Winston Churchill sums it up in The Gathering Storm: battles are won by the stronger army. If the forces are matched in strength, the more numerous army is the stronger army. If the forces aren’t at the battle, they don’t help much. So the front line delays the enemy while reinforcements move into position. To achieve a decisive victory, Wellington, Bismarck, Nelson, Rommel, and Napoleon arranged it so that their forces were more powerful than the enemy at the point of attack. Every once in a while, the balance of power shifts because of technology, but by and large, this game (war or soccer) is about logistics and doctrine. ISo all you have to do is make sure to always attack with overwhelming strength to achieve a decisive victory. If you have the ball, attack with overwhelming strength. If you don’t, slow them down until you do, and then take the ball away.

You might ask, “why don’t you just charge right in?” Blitzkrieg is an advanced tactic, reliant on France having no reinforcements (the mass of maneuver) in reserve to counter-strike. The coach you face won’t make that mistake.

That’ll get you from 6U to the first half of the 12U season. After that, we switch to Land War In Asia. More on that later.

Oh, no! How to turn this ragtag bunch of misfits into a team before Saturday? Regardless of age, here’s a formula that will get you through the week.

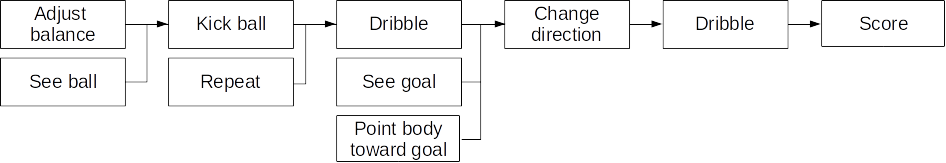

The first practice is a hasty dress-rehearsal. There’s no time for strategy, or even tactics, so double-down on the fundamentals. We can anticipate some of the behaviors that the kids will have when you get them. They’ll kick the ball and then watch it go. Or they’ll take a few steps back from the ball, take a deep breath, and charge at the ball. Most kids will have a dominant foot. Quite reliably, new players will kick the ball in whatever direction they happen to be facing. If we recognize that these are innate human behaviors, and not wrong, per se, we can build on them.

The team who scores the most goals wins, right? Start practice with dribbling the ball into the goal. Set up two goals (4' Pugg-style), about 25 yards apart, and slightly offset, and set up a circulation pattern. Run alongside each player, one at a time, and make sure she’s using both feet. Then, when she arrives at the net, encourage her to run all the way through the net after the ball. I’ll demonstrate it, and then act like a bug in a spider web, and say something witty, such as “I’m a bug, trapped in a spider web!” The 6th grade boys may roll their eyes, but I don’t mind.

Not rocket science. Just dribble the ball into the goal.

Why not shoot from far away, like they taught in the 1980's? Running over the goal line develops a habit of following through. Not infrequently, players will score unintentionally, just by the ball ricocheting off them as they careen toward the net. Better to be running toward the goal than standing still, waiting to make a decision. Also, it can prevent players from developing the habit of falling backwards after a power kick. For older players, 10U and up, have a parent stand completely still in front of the net and challenge the kids to go around the parent. This will reward finesse over strength.

Common things kids do and what to do about it

| prefer one foot | left, right, left, right, .... |

| stops to shoot | run all the way through the goal |

| can't change direction | look up |

| can't look up | "how many fingers am I holding?" |

| wide U-turns | step over and reverse |

| ball gets away | slow down -- red light, green light |

| backs up before kicking | hold player's hand and move forward |

Imagine what will happen on Saturday. The grass is fresh, the air is crisp, and the parents are yelling “Stop spreading out and bunch up!”

Wait a minute … nobody has ever said that. You see the ball, you go toward the ball, and then you are surprised to find everyone else there, too! Humans gather together automatically. The ball is like the kitchen at a dinner party, it’s where all your favorite people are! We’re going to take advantage of that and learn to play in close quarters. Once the team is comfortable with that, they’ll spread out on their own.

Why do soldiers march in formation? So that they arrive together. If you show up early, you’re outnumbered. If you show up late, the guy who was there first was outnumbered. The important thing is for everyone to arrive together, and that means moving at the same speed. So we’re going to teach our players how to do that.

You also never hear, “Stop sharing the ball with your team!” I learned from my kids’ preschool that, before one can share a toy, one needs to feel confident that it will be returned. So let’s practice that, too.

The next activity is called dribbling with a friend, or touch-touch-pass. The goals are still set up about 25 yards away. Two players will hold hands, and dribble the ball into the goal. The catch is, you can’t let go, and you may only touch the ball 3 times. The first touch traps, the second touch controls, and the third touch passes to your partner, who is only 18" away. Left, right, left. It’s harder than it sounds. If one player boots it, they both have to run together to get it back. If a player stops to watch, she gets dragged along. When a pair reaches one goal, switch hands and go the other way, with the other foot. Even if you have an even number of players, the coach can play along, too, and switch up the partners. In subsequent weeks, you can have both players hold a pinnie, to make the distance larger and the speed faster. When the kids are ready for more of a challenge, add a parent in front of the net, a cone obstacle course, or ditch the pinnie and add variations like 3-person-weave, give-and-go, 1-touch, or passing behind.

Two more specific skills that are important at the first practice: tackling from behind and changing direction.

Wait, what? Tackling from behind is against the rules. It’s very dangerous. But you’re going to see it happen on Saturday, because your player wants the ball and the most direct way to the ball is through that other kid. So I think it’s important, in the first practice, to teach how to get the ball away from someone running away from you. They key is to run alongside, match speed, and then slip between the player and the ball. We’ll teach just the last bit, while standing still. Divide the players into pairs. A stands in front of B. There’s a ball in front of A. With two let motions, B steps beside, and then in front of, A. Now B has the ball! Then A does the same to B. Watch closely, and you’ll see this maneuver takes most kids 3, 4, or 5 foot motions. You’ll need walk around and work with each pair. Some kids will want to boot the ball away as soon as they get it (impress upon them that we’re not trying to show who’s better — we’re trying to help our teammates learn a new skill). Others may need your help figuring out where to move their feet (point to a spot on the ground, say, “look here,” then say, “put your left foot here,” followed by, “let’s start over, but this time with your other left foot.”). Once they’ve succeeded once or twice, you’re ready to move on — there’ no need to practice it while walking or running.

The limbs of little kids aren’t necessarily under voluntary control. What teachers and psychologists call executive function, the ability to will your brain to do something deliberate, is a few years away. So kids tend to drift forward in whatever direction they’re facing. What we’re doing with these exercises is establishing connections between the individual limbs (left foot) and higher-level objectives (get in front) that weren’t taught in PE class because they don’t have PE class anymore. Over the course of the season, we’ll build on this vocabulary of motion to develop more and more sophisticated behaviors.

Finally, changing direction. A hallmark of recreational soccer is wide U-turns. So when I started teaching my players how to a step-over-and-turn, I was surprised to discover that most of them couldn’t step over the ball. You’re probably thinking, “that’s crazy,” but it’s true. The legs involuntarily go around the ball, not over it. So have everyone stand near a ball and mirror your moves. Step left over the ball, step right, front, back, turn around, etc. The important thing that your foot travels over the ball, not around it, without touching the ball itself. When the player’s feet go around instead of over, have your assistant coach hold out an arm above the ball, and the player can pretend she’s stepping over a log. A little light bulb should turn on in her head, and you can move on to the next player. This is the fastest way I’ve found for building body awareness in players up to age 12, and seems to help them maintain control of the ball on bumpy ground. Again, you only need a few minutes for this on the first practice.

Note, we’re not standing still and passing the ball back and forth. Nobody, not even the coach, stands still in soccer. Also, we’re not worrying about push-passes, trapping, screening, or power kicks. All that can come later. The first game is just “run toward the ball and then dribble the ball into the goal.”

With basic skills out of the way, it’s time to move on to the critical restarts that will happen in that first game: throw-ins, goal kicks, keeper restarts, and corner kicks.

While refereeing for a few years, I’ve noticed that players of all ages tend to fight over who gets to take the throw or kick. Some coaches will keep track of whose turn it is. Others will have the kids do it in order. This reinforces the mental barrier that the team is just a collection of individuals. I think the infighting stems from an underlying insecurity, a fear of missing out. To circumvent that, we’re going to build a narrative of teamwork and cooperation. Every restart drill is done with a partner, and ends with the ball going into the goal. If there’s any defense, it’s a coach or a parent standing stock-still in front of the goal. Not a fellow teammate until much later in the season. Furthermore, the partnerships rotate often so every player goes home with a memory of a positive shared experience with every other player.

Also, there are plenty of kids who don’t care about winning, so long as they get to hold the ball. Besides encouraging them to also try T-ball (everyone gets a turn as the center of attention), let’s create plenty of opportunities for our players to experience these restarts in a game-like situation. You can do these three exercises with the goals still configured for the running-back-and-forth that we opened with. As long as you remember each kid’s name, they’ll get to experience some of the thrill of being in control of the game.

For throw ins, have the kids line up on the touch line (this and shaking hands are the only time I ever have my team line up). Tell the first player, A, to go into the field a few feet away (put a cone there so she knows where to stand) and tell the next player, B, to throw the ball toward the goal so that Player A can run forward and score. Then B takes A’s place. When A scores, she joins your assistant coach on the other side of the practice area to do the same thing in the other direction. I usually go clockwise for the first week, but feel free to switch it up. After a few cycles, everyone will be in motion, and nobody will have Their Very Own Special Ball anymore, which you may have to mediate. Offer at most one recommendation on each pass, such as “if you bend your knees a little, it’ll be easier to keep both feet on the ground,” and “just throw the ball really hard toward the goal and your teammate will run to get it.”

In later weeks, we will add complexity.

Now that we’ve got the hang of a cycle drill, you can seamlessly switch to goal kicks. We’ve all heard parents and coaches scream, “don’t kick the ball across the front of the goal!” Fat lot of good that does.

And now, some psychobabble.

Don’t think of an elephant!

You’re thinking about an elephant, aren’t you? How often in soccer games do we hear someone shout “Hey Sarah, kick the ball over there!” Of course, she stops looks at you, because listening to a parent overrides all other cognitive processing. Moreover, she doesn’t see the people behind her, or which way you’re pointing when you say “that way.” Left and right probably are a little fuzzy, too. I’ve seen little kids walk into a pole because they were chewing gum. If you can’t walk and chew gum at the same time, you definitely can’t dribble, screen a defender, and listen to your mom. Remember what they say in the coaching class: the player most able to hear you is the one farthest from the ball.

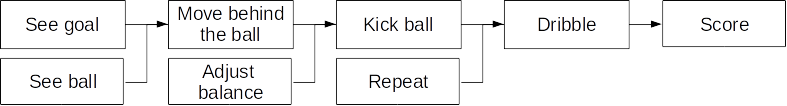

Let’s start a habit of taking goal kicks to the side, while becoming emotionally comfortable with receiving a goal kick instead of taking it. Player A takes a position by the goal line, away from the goal. Player B picks up the ball, puts it in front of the goal, and kicks it in front of A. After the throw-in exercise, B should know about how far to lead A.

Plant yourself near the receiver, and say something like this, “Charlie, let’s start back here so we can see the ball and where we want to go. Where do you go when you get the ball? That’s right, the other net. Good. Let’s look at that other net, and turn our bodies so we’re ready to run to the net. OK, we’re ready for the goal kick!”

As before, the ball finishes in the other goal, and the kicker becomes the next receiver. If you think the kids can handle it (12U, maybe), alternate the goal kicks between the left and right sides. It’ll be total chaos in the middle, but that’s part of the fun of learning to dribble through traffic.

Sometimes, the receiver will get so excited that she’s halfway across the field before the ball is cooked. Also, you’ll discover that kids, like dogs and horses, don’t walk backwards. You can address that another week with the Department Of Funny Walks game.

Our final reset is corner kicks. Not to overthink it, the basics are

As before, one player kicks the ball from the corner to a receiver player, who runs forward to put it in the net. The receiver, while waiting for the kick, will lurch forward in an unproductive direction. Just as with the goal kick, ask the receiver if she can see the ball and the goal at the same time. When she replies, “no,” follow up with “Where should you go so that you can see the ball and the goal at the same time?” End with, “That’s great, Barbara! Let’s go there.” You’ll probably walk over there with her and remind her to turn her body in the direction she wants to run. If nothing else, you’re introducing a systematic decision-making process.

I try to personally address each player with every message. While it seems faster to say, “Hey you guys, listen up! Do this,” nobody ever listens because none of them are named “you guys.” You end up saying that 10 or 20 times. In the long run, it’s more effective to have the same, heartfelt and personal conversation with each kid, one at a time, just as if you’re working in retail.

After a couple rounds, add a goalkeeper or defender. Don’t practice the whole set piece in the first week; just try to get the keeper to start toward the back post, so she has room to move forward.

If you’re coaching 10U or 12U, you might have just enough time left to show everyone where to go for a corner kick. But they won’t remember it so you could also just punt

By now, the kids will be out of attention and you can turn them loose to scrimmage. Let your assistant coach supervise that while you take a break.

Wait a minute. In 10U or 12U, you’ll also need at least two goalkeepers for the first game. The first priority is safety, so lead with the skills that keep the player’s face well away from the ball and any errant feet. While the other kids are scrimmaging, take one goalkeeper at a time through the basics:

What about the kick-off? Isn’t that an important set-piece? Not in a rec league. Who cares about conceding an early goal? You can talk them through it on game day, but they’ll probably come up with something they think is clever on their own. Might as well let them try everything and see what happens. Also, let the referee have the fun of talking the players through the flow of the game.

For the first few weeks, expect most goalkeepers to watch the ball go right by them the first few times. It takes a few tries in an actual game situation to be prepared to act in the context of all the noise and excitement. Just remind the parents that every goal conceded today means a stronger goalkeeper in the playoffs.

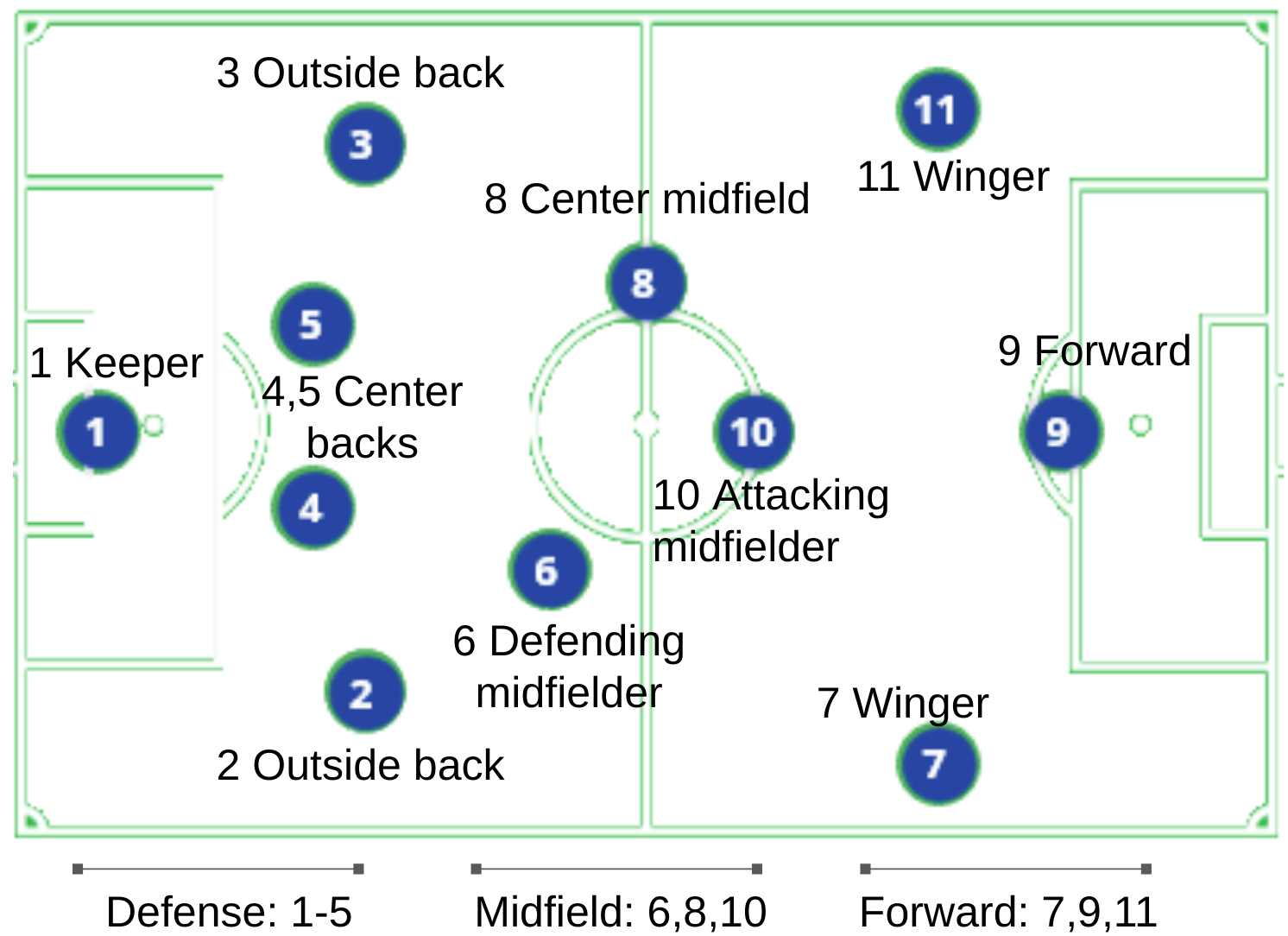

Coaches like to talk about systems of play, or how to position the players, as if the kids will have any cognitive surplus to spend on knowing where they are on the field. Forget that. Just run and kick the ball into the goal. To stake out territory before the kickoff, take your best player, your mass of maneuver, the Marine Corps of your team, and put her in the back. Your parents will ask, “shouldn’t you put the best players up front?” Nope. Attacks start from the back. From there, your best player can get to wherever she needs to be.

Most attacks will come up your left side, because most of the other team’s kids are right-dominant. So your left-dominant player will anchor your left defense (at least for the first 3 weeks).

Since you’ve been tougher on your own kid all week, you might as well give her the first kickoff. Everyone will get a turn eventually, right? Start the slow (it works for the LA Galaxy!) and timid players up front. That’ll save you from having to overcome their fears of playing forward, later on. Anyone who is fast, starts well behind the front line, so when they run forward to support a counterattack, they catch up with the forwards, and boom! Numerical superiority!

If you’re playing 12U (9 players), you can augment the midfield. I don’t even tell the midfielders what side to play, since they’ll all chase the ball together anyway. Sometimes, I ask the center forward to join the midfield bruiser squad. Then the left and right forward positions act as “wings” — outflanking the defense or slowing down a counterattack.

OK, you survived the first week. What next? Of course, I have spreadsheets of all my practice plans. But first, some psychology.

For the first practice, I asked you to do some very, very brief skill training. At most, 10 minutes for each activity. That’s because people actually learn quite quickly, which researchers at the NIH have been able to study brains as they learn new skills with Functional MRI. His tells us that the first time you try a new skill, you only need to do it for a few minutes [1], so long as you do it correctly. Immediately, those skills go dormant for about 2 weeks while the brain reprograms itself. Only after that process completes is repetition meaningful.

Keeping this in mind, premature repetition drills can actually be harmful. If a child tries a new skill several times, chances are, one of those times it’ll be wrong, and that’s what her brain will remember. You can avoid your players having to unlearn bad habits by coaching one-on-one, the first time, and then stopping altogether as soon as it’s perfect. Reinforce this with “That was excellent! Stop right now and don’t try it again at all today, so that your brain remembers what it was like to be perfect.” It also helps to remind the parents to please not try to help by making their kids practice at home.

Functional MRI research also provides some strong evidence that nobody learns passively[2]. Even when you’re watching soccer videos, your brain activates your motor cortex to simulate making the motions yourself. So your brain acts like it’s playing soccer, only without moving your feet. And we’ve already observed that nobody is named “everyone.” The most effective teaching method is to walk alongside one child at a time, talking her through it. Do it once for each kid, for each skill, and you’ll save time in the long run.

For the first few weeks, I go quickly through basic skills and set pieces, starting easy (do it right the first time), so that everyone would know where to go and what to do during a game (goal kicks, corner kicks, throw ins, kickoffs, …). There’s very little repetition, except that every drill ends with a player dribbling the ball into the goal. By week 4, just about everyone on the team will be able to run with the ball under close control while looking where they’re going (toward the goal).

You may hear parents say, “but she did it so well at practice yesterday!” An experiment on rats suggests[3] that what the players learn in those moments may only show up much later: “changes in map topography that endure beyond the training session are not detectable until after 10 d of training.” Sure, human brains are different than rats’ … but not that much. So if you have a good practice, don’t expect anything to happen on Saturday. Or even at practice the next week. But you might see it at the following game or the practice after that. What that means for us coaches is we should follow a 2-week tactical training cadence, where each week’s lesson doesn’t build on the previous week’s, but on the practice that was 2 weeks ago. After the kids’ brains have had time to incorporate the new skill (changes in map topography), repetition drills become meaningful.

Your child’s teachers may have told you about the principle of scaffolding, that new ideas build on established ideas, and complex behaviors are built from combinations of simpler ideas. Only in 2011 did scientists at MIT figure out that the brain has only four slots of working memory, two on each side [4]. Moreover, they showed that this is a bottom-up limitation, meaning that it’s not something you can override through willpower, but a fundamental limitation of the system that our brains use to store and process information.

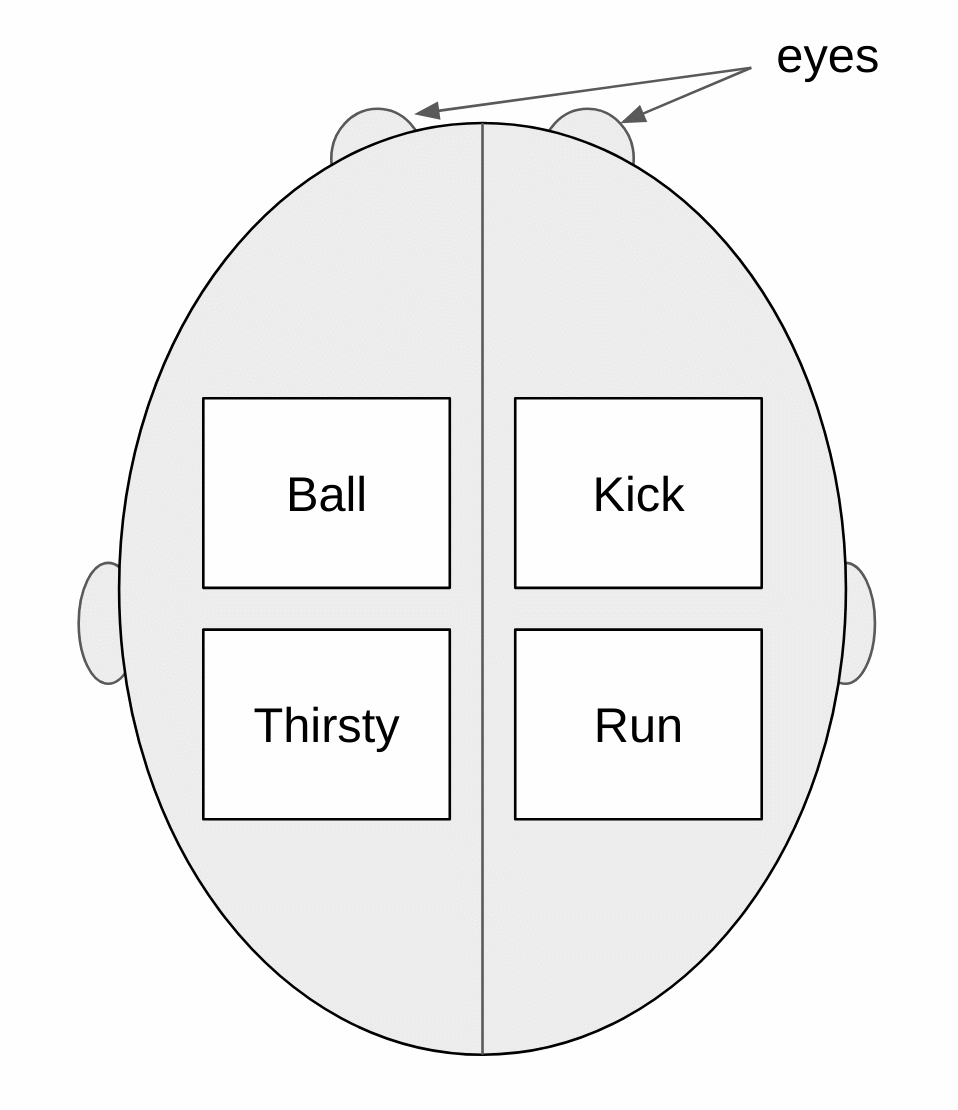

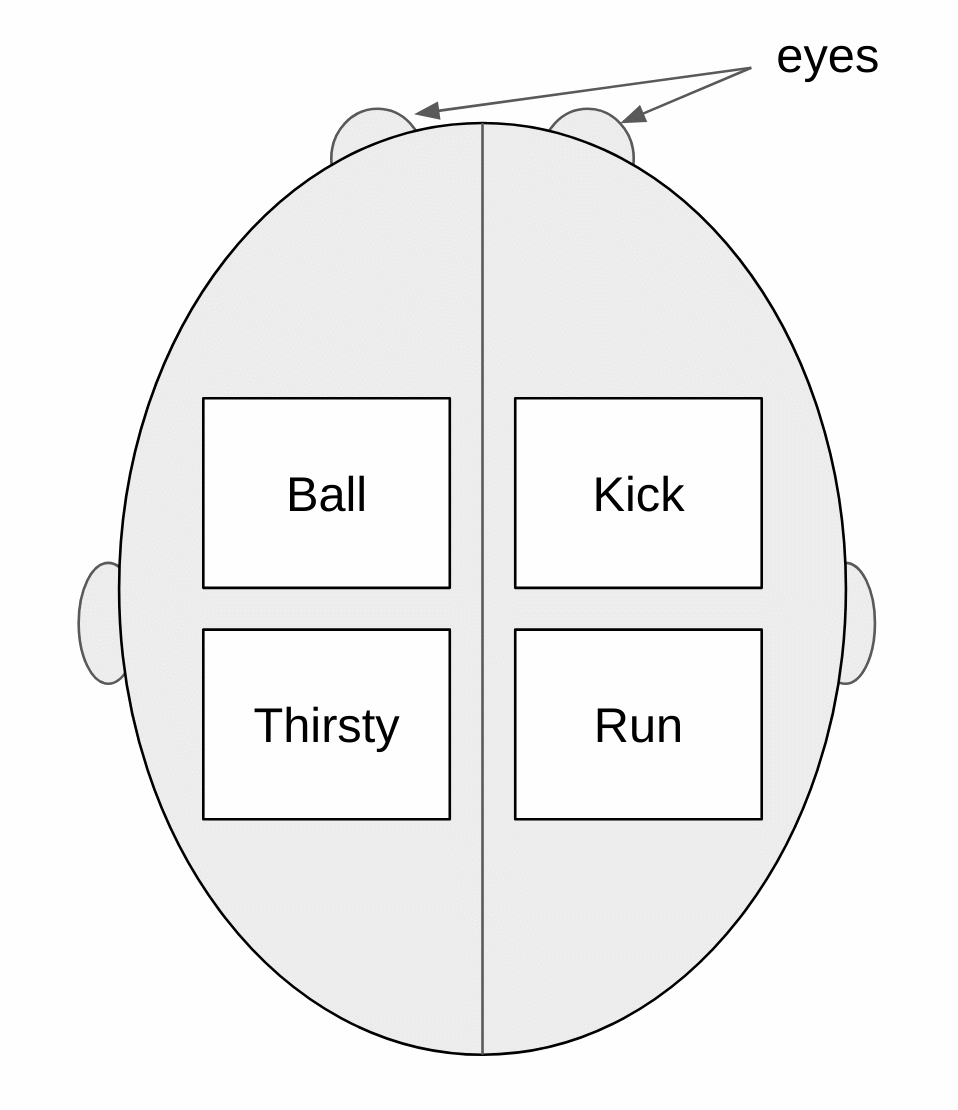

So let’s imagine a child who is completely new to sports, and we’ve just done a great job teaching basic skills in practice. Here’s what might be in her head.

What happens when the game starts, and everyone starts running and shouting? Higher-priority ideas take over. Many of your players will literally jump up and down while flapping their arms, watching the ball go by them. Overwhelmed by excitement, they’ll be unable to move until after their minds process the new events. As a coach or parent, it can be exasperating, so try to think of it as a necessary developmental stage that prepares them to better handle a similar situation next time.

Maslow’s hierarchy of needs reminds us that before our players can think about teamwork, they first have to satisfy their basic body function and safety desires. (Always good to remind a team to use the restroom before the game starts). When we start the first practice with “run kick the ball into the goal,” we aim to compress 3 ideas (ball, kick, do it again) into 1 (dribble). Then the goal comes into view and we compress 2 ideas (dribble, goal) into 1 fairly sophisticated idea (run kick the ball into the goal). We hope that, on game day, that one idea will give us a functional soccer player while leaving 3 working memory slots available for observing and understanding the experience.

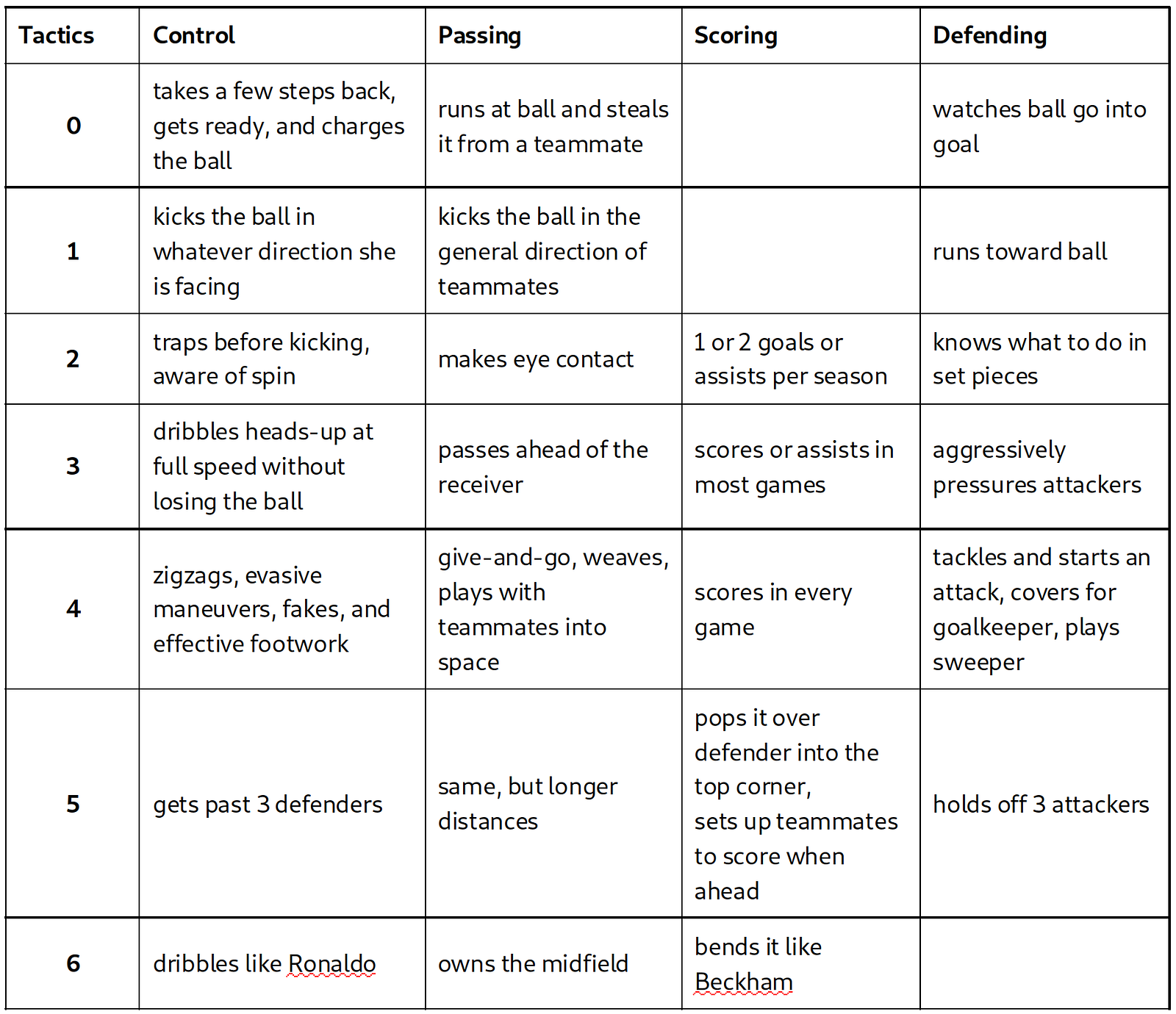

Bill Owen has been a soccer volunteer for so long that they named a tournament after him, the Bill Owen Spring Classic in Pasadena. Bill lists a very simple progression of skills that we can guide our players through.

Imagine you start the kids dribbling without a goal. What is the scaffolding that will allow them to score? While they’re already dribbling, the player will have to change direction, which involves synthesizing 3 ideas, and a transition between stopping and restarting.

If, instead, you ask a beginning player to look at the ball and the goal at the same time, her feet will arrange themselves so that her body is behind the ball. Then, she can arrive at the objective (kicking the ball into the net) with only ever having to use 2 slots of working memory.

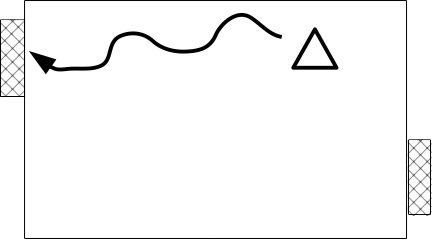

Fewer steps, and fewer working memory slots, so a better chance of it working, especially in the first week. Some players will still arrive at the other end of the field, surprised that the net is way off to their side, but most will go more or less in the direction they started off in. The team will eventually need to learn how to change direction, a sophisticated behavior that involves 1) listening and looking, 2) deciding where to go, 3) trapping the ball, and 4) redirecting the body’s momentum. Week 2 seems like a good time to start on that.

Call it ball control instead of ball handling because only goalkeepers should be using their hands.

If the first practice was to walk through the flow and set pieces, the second practice is your chance to introduce skills that the team will build on for the rest of the season. At the game on Saturday, you can also expect some parents to get swept up in the excitement and start coaching from the sidelines. The most common, and unproductive, admonition is, “Pass!” Parents can see the full field — who has the ball, who is open to receive a pass, and who is approaching to apply pressure. But the child with the ball can only look forward. She can see the ball, and maybe the goal. She probably can’t see those other people, and even if she could, we haven’t yet installed the brain circuits to enable her to process what to do about it. Fortunately, the players can’t hear most of it.

While passing in a game situation is still a few weeks off, we can lay the groundwork by building relationships as we work on basic skills.

As always, a good arrival activity is dribble the ball into the goal. The attention spans are short, so prepare more activities ready than you think you will need.

Dribble the ball into the goal. Just what it sounds like. Encourage running through the goal (pop-up Pugg, right?) to follow up rebounds. Recruit parents to stand in front of the goal as stationary obstacles. Add slalom cones in front of the goal.

Dribbling with a friend. Pair players according to the side of the field they will play in the game. Field setup is the same as Touch the ball twice (trap, push forward) and then pass to a teammate. Work toward matching speed and passing in front.

Department of funny walks. The coach demonstrates a funny walk, and then the team copies it. Alternate players and the coach proposing the walk. Coach’s walks include: shuffling sideways, walking backwards, lurching forward and stopping,

Dribble around the world. Cones are arranged in a circle. Everyone dribbles around the circle without losing the ball. Then change directions and use the other foot.

Water break!

Step over and turn. Coach demonstrates and players copy: step over the ball, then step back, then side to side. Once they get that, step from the side to the front in a quarter-turn. You’ll probably need to show kids individually how to change direction by rotating their feet as they step down. The dancers on your team will be best at this.

Dizzyball. While you have everyone standing next to their ball, try shuffle around the ball while keeping it in front of you, without touching the ball. This is the foundation of what 5-year-olds like to call the butt defense, and everyone else calls screening. It’s easy to explain that you put your bottom between the ball and the opponent. As the opponent (the coach) moves around, the player shuffles around the ball, blocking your access. Do this with coach as the defender, not other players, or you’ll have to listen to them complain about getting their legs kicked.

Sharks and minnows. Same circle of cones from around the world. Everyone has a ball but the shark. Call “3–2–1-Shark Attack” and the shark tries to kick the ball outside the circle. Lose your ball, and you become a shark. Last player with a ball is the next shark. Good game to do before a water break, because otherwise you’ll never get them to stop.

2v2 Divide the practice area to try out those ball-stealing and screening skills. Restart with a goal kick, and leave it up to the players to decide how to restart play when it goes out of bounds. A small area with small goals requires control. You could use the pop-up goals for this, but I’ve found that simply using short cones works better. Anyone who scores by kicking the ball really hard gets to run get it, which quickly leads to shorter and more accurate scoring. This is about control and finesse, which will score more points for you on Saturday.

Water break while you move the goals. With any luck, the players will be a little tired.

Power kicks. Most people call it an instep kick, but power kick is more descriptive to a 5-year-old. The power kick has too many moving parts, so all the advice I can find involves a coach helping the player experience what an extended, locked ankle feels like. Guide each player through the motion of slightly lifting her hip to swing the laces through the ball with the ankle locked. Anything else just gets you a lot of toe kicks. Brown and Narvaez of Michigan State University describe how to do it in detail. It’s good do to this after a water break so the coaches can work with players one at a time. Set up all the goals together, and put a line of cones across the field. Players kick balls while their parents shag the balls back to them. With a pop-up goal, you can simply lift the goal and shift it to the side to extricate the balls. Return the balls into an open space, to make them run, because nobody stands still and waits for balls to come to them in soccer. Expect everyone to fight over using their very own special ball. Learning this skill shifts motivation back to basic needs. The aim will be terrible. Wait a couple weeks doing it again.

Scrimmage. Set up really wide goals to get many chances to practice the kick-off — the one set piece we haven’t done yet.

8U is pretty much like 6–7, except there’s one rather complicated game that this age group likes and is mature enough to pull off.

Tigers in the jungle. Everyone picks an animal, except tigers. Everyone has a ball, except the tiger. The tiger tries to kick everyone’s ball away, and then roar like a tiger. When she succeeds, the player runs to get her ball, holds it over her head, and makes her animal noise until someone else (not a tiger) dribbles a ball through her legs. Trust me, it’s a hoot.

Dribbling with a friend. As above, but holding hands. Now they really have to match speed! Two attackers are better than one

I start out with the first two, and then see how it goes to choose the rest of the skills.

Dribbling with a friend. 10U players are only 7 or 8 years old at the start of the fall soccer season. They still like holding hands. So start with pairs holding hands. As they get better and faster, have each hold one end of a pinnie. If someone lets go, they have to reconnect before they can reclaim the ball.

Gates. The best activity for building heads-up attacks. Arrange cones to make gates, about a foot wide, scattered willy-nilly about. Partners each hold onto a pinnie and take turns passing the ball to each other through a gate, then quickly move to a different gate. See how many you can get through in one minute. It’s a stretch for 8U players, and a must for 10U+. After they’re good at it, do it without the pinnie.

Department of funny walks. The coach’s un-funny walks are standard running drills: high-kick stretches, side-shuffle, side crosses, running backward, high-knee. Ask the players to suggest ways of running that they already know. Noises and facial expressions can make it fun for you. This will only work once at this age.

Taking your ball for a walk. Segue from funny walks and add a ball. Roll your foot over the ball, maintaining contact with one foot or the other. Resembles an emperor penguin waddling with an egg. If the field is painted, try to stay on follow a line with interesting turns. Or, meandering follow-the-leader with turns and direction changes. If it’s going well, switch to sideways or backwards.

Change direction on a box. Wide U-turns are still big in 10U. After doing the “how to step over the ball” skill, try that on a 10' square of cones. Dribble from corner to corner, then quickly execute a 90° turn. You’ll probably have to guide the legs of each player through it: step over the ball to stop it, then gently push forward in another direction. Call out direction changes as players approach corners to force 180° turns.

Tackling. Facing a partner, and one ball, count 3–2–1-kick. It’s good for the coach to take a turn with each player. When the balls stop flying around, have everyone back up a few steps and walk into it. Important to dial down the competition and stress: we’re helping each other learn a new skill.

Ping pong. The ball will go in the air, and you can’t use your head. Get ahead of that by playing the ball in the air with control. Players stand about 10' apart and volley it back and forth. It’ll be tempting to kick a wildly spinning ball. Stress trapping and kicking on the bounce. Slap-downs to bounce the ball back up, traps with shoulders, and traps with hips work. Use both feet. They’re going to try roundhouse kicks anyway, so you might as well have them learn how to control it. No falling-on-your-backside bicycle kicks. Beware enthusiastic kids who back up really far to make big kicks. Start small and controlled by counting how many volleys each pair can make in a row. Trade partners every few minutes.

Water break.

Corner kick. This is an offense-vs-defense drill, and the important thing is not winning the corner kick, but resetting quickly to do it again. The habit of rapid restarts will allow your team to get more practice in the same amount of time for the remainder of the season. For 10U, do 5v4 (defense is outnumbered). For 12U, two groups of 3v3. Put all the balls in the corner. Move the offense back away from the goal so they have room to run forward when the kick is taken (you’ll have to move them back at every reset because kids don’t walk backwards). The goalkeeper’s feet will drift to the near post, leaving the back post wide open. Move her back every time. The defenders will forget to guard the near and far posts. Move them back every time. Tell the kicker to just put the ball across the goal and the attackers will run in. If she whiffs it, try again. Remind the kicker to run in after the ball to support the play. If defense gets possession or kicks it away, the defense wins, and you yell “Restart! Just leave the ball there! Places, everyone! Places!” Each player gets two tries to be goalkeeper and to take the kick.

Power kick. A low-intensity activity, the same as with 6U, only now with parents having to run further to retrieve the balls.

Pass in front. At walking pace, pass ahead into space.

Scrimmage. Stand back and see what happens. Shuffle sides after every point.

This week’s theme is, the best defense is a good offense, even if you’re the last defender. Don’t stand around waiting for the ball to come to you when you can interrupt an attacker’s thought process. If you’re all alone, they were probably going to score anyway. If not, your defenders will cover the open holes.

It may be tempting to start the game hot and win early, having your best player charge through their unprepared defense, but it’s better to use the start of the season to set solid skill foundations for later. So I start the strongest in defensive positions, to establish the habit the of attacking from the back. If the other players can fall in beside or behind, it will help develop trust among the team. A brute-force attack up the middle with superior numbers isn’t pretty, but it gets the whole team involved.

Every player does some things well, and positive coaching means building on those strengths over the course of the season. I want my team to play like the Belgians — players change positions faster than an Italian player can make an espresso (I swear it was funny in the coach training class). That way, any combination of players can recognize and take advantage of a breakaway opportunity, and the rest of the players will fill in the gaps they create, as needed. Necessary prerequisites, in order:

Those are some pretty big steps, so I break it into smaller objectives that I track for each player. Toward the end of this document are some rubrics that you can use for predicting what each player’s next step will be.

On an ongoing basis, my teams are always refining basic skills, introducing new moves, and talking about tactics and strategy. I don’t do “give-and-go” plays — only a vocabulary of positions on the field that the players can use to improvise. We mostly use the set pieces to develop those, so the goal kick scenario will turn into a 3-on-3 scrimmage that restarts every minute or two.

One more thing — a number of parents have noted that I permit the players to walk around while I’m talking. Two reasons for that:

When I want their undivided attention, we’ll all kneel for pre- and post-game briefings. That’s another sort of set piece, and that’s when I say what I want the kids to remember when they’re not playing soccer.

Everything we do in practice is a part of the game, and most drills end with the ball in a goal. I avoid contrived activities — only vignettes of an actual soccer game. At no point in a soccer game do people stand around passing the ball back and forth. Well, maybe the French national teams do. But I want to play like the Belgians — always in motion, learning every position, and difficult to predict. Therefore, skill practice happens while running.

By week 4, the kids will show up to practice and, instead of asking “what are we doing today?”, they just start dribbling a ball into a goal, over and over again. On game day, they dribble the ball into a goal, over, and over, and over.

So at first we practice all the set pieces — throw-ins, goal kicks, corner kicks — with balls ending up in a goal somewhere. After a few weeks, we introduce complications like knowing where to stand, leading the receiver, running to create an opening. Those drills are really difficult and require patience from everyone to make them work, so we interleave them with easier, specific skills.

When we teach a new skill, I don’t mind that most of the team is somewhere else running around like crazy people. They are happy to have a ball, and to have each other. Building those friendships helps them feel comfortable cooperating during a game. Meanwhile, that frees up the coaches to work individually with one player at a time. And when they get it right (today it was zig-zagging, which meant you had to use BOTH feet), we stop and direct them on to something else. That way, the last thing your player remembers is doing the skill correctly, while moving toward a goal net. Her brain will move that memory into long-term storage overnight.

We’ll come back to that skill after two weeks and then, and only then, try to make it go faster and better.Weeks 3–5

Emulating Chelsea, AYSO prescribes a simple formula for practices:

We didn’t do this before, because we wanted to prepare our players’ minds for learning more efficiently, later in the season. For week 3, you might choose to work on restarts

The 4-stage training progression is an effective system, especially for protecting the coach’s sanity. However, no plan survives contact with the enemy. When you try this with young kids, you’ll quickly discover that not only is 10 minutes of any single activity much too long for their attention, but they lack the skills to get very far anyhow. To resolve this paradox, have a library of technical interludes that you can intersperse between the steps. Some are outlined in Practices #1 and #2, and here are some more.

Power kicks. It’s good to do this every couple of weeks anyhow.

Change directions. Four cones are set up in a line. Players start at each end. Dribble forward to the next cone, pass to the other player, and quickly run back to the starting cone. Repeat.

Tap the ball. Harder than it sounds, to just tap the ball with your foot. And then do it again. See how fast you can do it without moving the ball. It’s a prerequisite for many advanced attacking skills.

Rolls. Roll the ball back and forth under your foot. Harder than it looks.

Aerial passing. Try to receive a pass with a trap with one foot, then pass back, without touching the ground.

Pass behind. Pass behind your own leg.

Step over and turn. Step over the ball, sweep the ball back with the other foot, and presto! You’re heading the other way!

Dribble spin. Can you dribble while spinning and rolling the ball under your feet?

Mirror. One player shuffles from side to side, changing directions and speeds, and the other player mirrors her actions. Then switch. Funny hand and facial gestures work on eye contact and peripheral vision. Eventually, add a ball or two.

Tackling. 3–2–1-kick

Butt defense. Everyone else calls it screening. I call it “sticking your butt between the ball and the other team.”

Keepaway. Just play 2-on-1 keepaway.

Kneeling throw-ins. Ball goes farther!

Dribble like Ronaldo. He doesn’t actually dribble — he passes forward to himself and zigzag runs nearby,

King of the box. Everyone in the box has a ball. The box gets smaller. Last one with a ball in the box wins.

Ping pong. This is how Ronaldo warms up — short volleys back and forth. Since you can’t teacher headers (and you shouldn’t anyway because, like punting, they usually result in a loss of posession), your team needs to learn to play balls in the air.

Zig zag. Dribbling with all surfaces of the foot in a non-straight direction

Sprinting. Running fast is about a) leaning forward, b) hitting the ground hard with your feet

Heads! When someone yells “heads up!” it means “cover your head,” not “look up so the ball hits you in the nose.” You actually have to teach this.

Tuck and roll. Do headers cause concussions? Maybe. Not as much as landing on the ground after a fall at full speed, though. So teach kids how to fall. Tuck and roll — tuck your head AWAY FROM THE FALL — and roll instead of breaking your arm. It’s surprising how much practice this takes.

Remembering that the mind wants a 2-week training cadence, it’s “what did we do 2 weeks ago, only more advanced”

Week 3, ball control

Week 4, speed and agility

Week 5, ball control

Week 3, revisit the set pieces. Close control of the ball (on your own, red light, green light — keeping the ball close). Quick restarts on throw-ins. Crash through the goal with the ball instead of shooting from too far away (sets the stage for follow-through).

Week 4, mobility skills. How to sprint (monster walk, lean in). Changing direction (zig-zag, step over and turn, leverages turning from week 1). Add a ball.

Week 5, positioning. From various field positions, do we attack or defend? Who needs to go where? How exactly do we coach that? Set pieces: where to go in corner kicks. Close-in keeper support (circle around back from the goal line so your momentum carries the ball away from your goal)

Red light, green light, ____ light. Keep the ball close so you can that you can stop it with the bottom of your foot when the coach says red light. On your team name light, go nuts and shoot on goal. Eerily effective at all ages. For 10+, use “how many fingers am I holding up” to train situational awareness.

Monkeys and alligators. The moat is full of alligators, and the monkeys have to run through without being tagged

Whack-a-mole. Small court, 10' x 20', with a midline. Two players on each side, and 4 balls. Object is to have all the balls be inside the court on the other side. If you kick it outside the court, you have to run get it. Hilarity ensues.

This is the point in the season where the parents lose their minds and start picking fights with the coaches and referees. It’s the week when the players are cocky and it’s the week when most of the referee abuse reports are received.

I feel very strongly that team practice should be cooperative, building common experiences without pitting teammates against one another. Elimination drills are not on my menu, and whenever we do 2v2, we rotate everyone through each role in the drill.

How can you possibly be a positive coach all the time when the players are so exasperating? As coaches, we can point positive. Point at the ground where you want the kid to go. The eyes will follow, and then the feet follow the eyes. If they’re not looking at you, move into their visual field. Then you point at the goal where you want the ball to go. No need to draw attention to mistakes or distractions — just point positive.

Week 6 is the doldrums. The novelty has worn off, and you’re a little tired of juice boxes. Time to shake things up. A good time to introduce deception.

The dribbling will get sloppy, so it’s a good time to start over. Trapping, dribbling, passing, only with fewer steps

Also, it’s a good time to introduce some fancy footwork moves. I have no particular skill at this, except to note that most of the cool moves on YouTube rely on a simple motion vocabulary:

Pick any two to do together and call that a drill.

Soccer is a thinking game, remember? You win by 1) aerobic conditioning, and 2) an information advantage.

The OODA loop is the most important piece of military doctrine since The Art of War. It describes a decision as the sequence of Observe, Orient, Decide, Act. The cornerstone of John Boyd’s theory is that is necessary to both Observe and Orient, in order, before a decision can be made. Your goal, as a soccer player, is to interrupt your opponents’ decisions so that when they get to Decide, they have to go back to Observe and start all over again. Go ahead and read all about the OODA loop on Wikipedia and devise a strategy for giving your team an information advantage.

Goalkeeper: Charge the attacker and give him less time to think. The ball was probably going to score anyhow — might as well try to fluster the striker.

1st Defender: Just keep moving your feet. Change your balance. Make the attacker look at you instead of you looking at her.

Defender: You want to be facing toward the ball and away from your goal, not toward your goal. Then the attackers have to watch you as well as the goal.

1st Attacker: Go right for the goal, and keep moving forward for the rebound.

Attacker: Fall in behind the 1st attacker to recover if she loses the ball. Then the defenders have to watch you as well as the 1st attacker.

If you develop a team that works together, they’ll figure out tactics on their own. What they need your help is to help them feel comfortable acting without certainty in the outcome of their decision.

Huh? Some examples:

If you’re coaching 7U or 8U, a child might complain to you, “nobody passes to me!” You would be forgiven for pointing out that she’s hanging out in a defense position in front of her own goal, and the whole point of her team is to send the goal the other way. But even if she does run forward, her teammates with the ball is unlikely to pass, because she’s already using all of her mental powers to keep kicking the ball in the same direction while everyone is screaming at her.

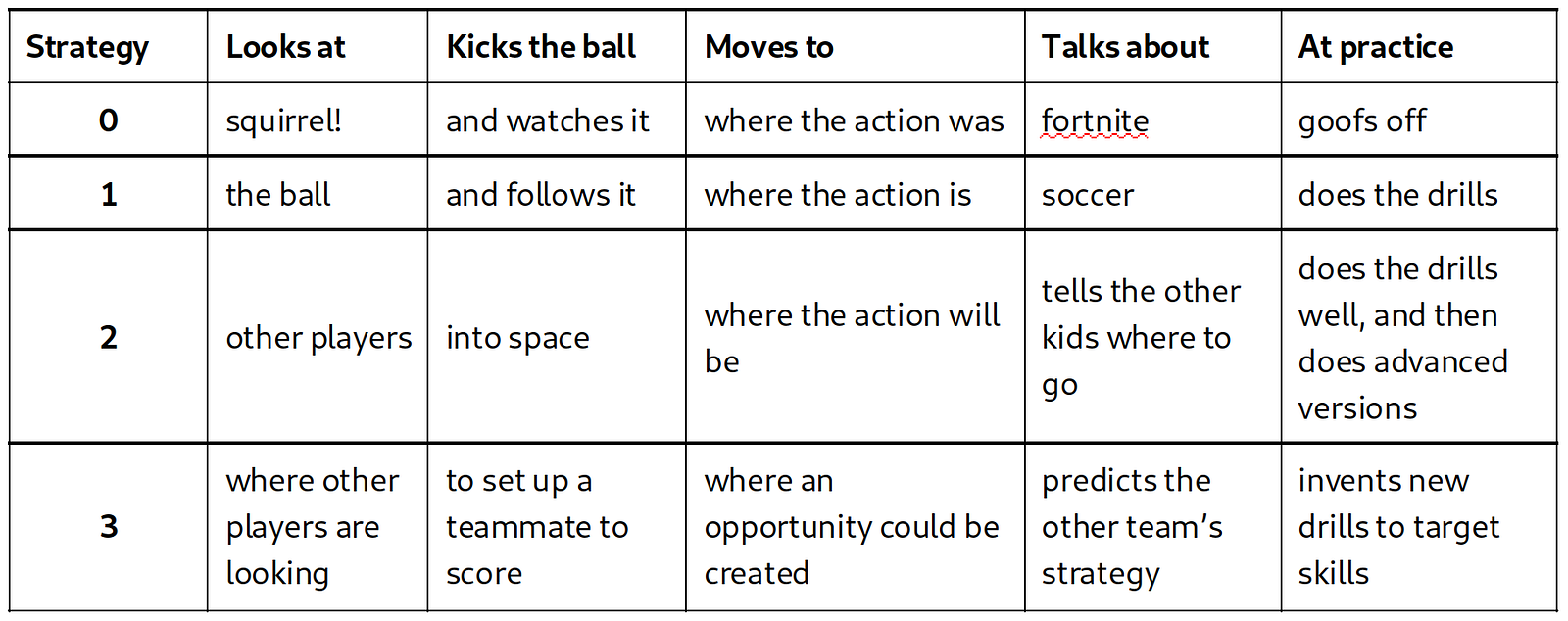

Consider what would go into a decision to pass.

1. Observe: the ball, the goal, the other team, and my team

2. Orient: I am running, the defenders are running toward me, and

my teammate is running alongside me

3. Decide: I would rather pass to my teammate than try to go

around this defender

Early on, players will only observe The Ball, which means they’ll never get to Orient or Decide. Not much you can do about that other than individual dribbling practice to give them time to get comfortable with The Ball. You can set the stage for more observation by challenging your player to watch the goal as well as The Ball.

It can be difficult to see and process the Other Team. Even in 12U, players will attempt to run straight through defenders, and then act surprised that it didn’t work. Famously, Joseph Banks, a scientist sailing with Captain Cook in 1770, noted that the natives paid no attention to his enormous sailing ship. Was it because, having never seen a ship before, they had no neural circuits for recognizing a ship? Or were they just too busy surviving? Regardless, position parents, standing still, in front of the goal, or scattered around, to train your players to observe and avoid obstacles.

To be unpredictable is to act without appearing to have enough information to make a decision. It is also the foundation of air combat, interrupting the opponent’s OODA loop. It is how Kasparov plays chess against computers. Hence, the Crazy Ivan, a sudden change in speed or direction. You can do that while dribbling (Mirror and 1v1 games) or by chipping the ball (Ping-pong). Even defenders can rapidly change their body position.

At 10U-12U, I spend a lot of time on ping-pong. Let’s say you flick the ball forward. You probably don’t know where the ball is going to go. But that’s ok, because you have an information advantage. You felt the ball on your leg, so you can probably get to where the ball is going a step or two before the defenders will.

So the first part is developing habits that give your team an information advantage. The second part is for your mind to move quickly with Observe, Orient, and Decide, and get to Act before the other team does. The way we do that is with cycle drills that keep everyone moving, to get more touches on the ball instead of waiting in line.

During games, I like to have the bench players sit next to me, so we can discuss what’s happening on the field.

Me: “Looks like we have a hole on the right side of the field. Who should move to cover that?”

Player: “Max is closest. He could step over a little bit”

The format follows the Socratic method

The peanut gallery behind you on the sidelines is always screaming at their kids to keep their eye on the ball. How can a player do that and also see her own teammate behind her? Or even beside? The view from the sidelines is much clearer. Mirror practices moving while looking around. If the eyes are the window to the soul, watching your opponent's eyes often tells you more about what's about to happen than watching the ball. I once coached a player who was so lazy, he could reliably count on the opposing team to pass him the ball. I don't know how he did it, but it worked. Dribbling With A Friend practices the integration of peripheral vision into a decision.

Anyhow, passing is often a terrible idea, because the fields are lumpy and your teammates aren’t very good at receiving passes yet. When the players are confident in their and their teammates’ abilities, they’ll pass the ball.

At this point, my practice plan notes get vague. It’s about responding to what you observe in the game, and repeating the activities that you’ve done before. Tactics become important, like being patient in defense instead of Kill Ball. Possibly the most effective practices are almost entirely scrimmages, with light intervention by the coach to correct technique.

Week 7, coordinated attacks. Close-in ball control, small gates, push pass

Week 8, initiative. Small-sided games. 2-person passing attacks. Introduce the weave in 8U

Week 9, positions. Precision passing — zigzag around defenders into goal

Week 10, cooperation. Box passing, Power kick, Side shuffle & defensive positioning, monkey/alligator tag, 2v2 games, cooperation

Week 11, support. Fast breaks without stealing from teammates (run alongside or behind). Pass across the goal, Kickoffs, Step over the ball

With any luck, you’ll get more players wanting to play in goal. For safety, I want kids to practice goalkeeping with me for a few weeks before doing it in a game.

Week 1: Safety. High catch, low catch, lob catch, turn-and-squat. Fingers together, elbows bent. Where to stand (not on the goal line)

Week 2: Fast balls coming at your face. 3 breaths before restart. Where to stand (constrain the attack angle).

Week 3: More turn-and-squat. Run toward attacker, cutting off options. Play 1Q in a game.

Week 4: How to throw the ball back into play (“distribution”) so your teammates aren’t surprised by how it bounces. Play 1H in a game.

Week 5: Add lunges and dives

Lower your expectations! With all the yelling and excitement, playing keeper in a game situation is totally different from practice. All the good keepers I’ve trained started off terribly. Expect a new keeper to let the first 5 goals go right by her, while she stands, immobilized, observing the commotion. Early on, a goalkeeper might get his gloves tangled in the net, watch the ball go between his legs, or be tying a shoelace. Actually, that was all one person. But who cares? After everything that could go wrong, did, he did great in the playoffs.

In Region 13, we’ve come up with what we think is a development-focused assessment framework. Print out a copy of the table, and for each player, each week, note what you think that player’s next step in development is. Not what they do well or do badly, but what you think they should work on next. See the Appendix below for my idea of the hierarchy of tactical and strategic development.

If you have a chance to get trained as a referee, go for it. One of the mantras you’ll learn is that the laws of soccer aren’t about who did what — they’re about what we do next to keep playing.

If you don’t think you have a good chance of winning the tournament, then play your favorite games at the pre-tournament practice.

But if you think you can win, and the kids have the hunger for it, and you don’t get rained out, then it’s time for grit.

4 simple steps to winning the post-season tournament

1. Expect panic. Tournaments are exciting, and panic takes over. Perfectly rational players will boot the ball to the center of the field, into a crowd of 5 of the other team, desperate to get it to your strongest attacker on the other side of that crowd. You can yell, "pass the ball to your own team!" all day long, with no effect. The brain stem takes over, and the kids get tunnel vision.

2. Posession. How can you prepare kids to overcome that? Hopefully, you've been drilling 2v2 or 2v3 all along, so that once they get past the jitters, they have some solid ball control technique and short-distance passing to rely on. This would be good to repeat in practice, because the big plays aren't going to come out until the team has a lot more experience.

3. Full-court press. You can also expect the other team to have the same deer-in-headlights experience. Take the fight to the scoring third of the field by having your forwards interrupt the opponents' attacks. Sometimes, the mere presence of a wild-eyed maniac bearing down on them will make a defender whiff a kick, leaving the manaic can have a 1v1 with the goalkeeper. If your team can crowd the center of the penalty area, the ball is bound to go into the goal. It can be difficult to persuade the forwards that their job is to play defense up top, not just stand around and wait for someone to pass them the ball, but that's what makes a winning team.

4. Go wide. If you the other team's coach feels the same way, you especially want your defense to advance the ball up the sides rather than up the middle (where the other team is crowding the center). One way to do this is to train your strong midfielders, the ones who can dribble the ball, to move to the sides on a change of posession. When the defense is afraid and looking to be rescued, make sure that rescue is running toward the wings.

5. Penalty kicks. One year, one of my teams finished the round robin near the bottom of the pool, which is pretty impressive in a pool of 36 teams. The odds were strongly stacked against us, and outscoring the other guys in the tournament wasn't going to be an option. We drilled keeping possession in unbalanced circumstances, with a lot of short passes. They played patient, scrum-like posession ball, ending every game in a tie. That turned a disadvantage into a fair fight: Kicks From The Penalty Mark. Fortunately, we had practiced penalty kicks a lot, and they used them to win every game, including the final.

It’s easy, and tempting, to overcoach your own kid. Most coaches will, for the first few years. Here’s an article about it. In summary:

This article was inspired by Paul Geller’s article, Better Fundamental Baseball. It’s also a simple game with endless variations, so Paul encourages us to coach a handful of fundamental skills, each practiced within a vignette of the full game, so that players gain an advantage by reacting faster when facing similar situations.

[1] Avi Karni, Gundela Meyer, Christine Rey-Hipolito, Peter Jezzard, Michelle M. Adams, Robert Turner, and Leslie G. Ungerleider, The acquisition of skilled motor performance: Fast and slow experience-driven changes in primary motor cortex, PNAS February 3, 1998, vol. 95 no. 3

[2] B. Calvo-Merino D.E. Glaser J. Grèzes R.E. Passingham P. Haggard, Action Observation and Acquired Motor Skills: An fMRI Study with Expert Dancers, Cerebral Cortex, Volume 15, Issue 8, 1 August 2005, Pages 1243–1249, https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhi007

[3] Jeffrey A. Kleim, Theresa M. Hogg, Penny M. VandenBerg, Natalie R. Cooper, Rochelle Bruneau, and Michael Remple, Cortical Synaptogenesis and Motor Map Reorganization Occur during Late, But Not Early, Phase of Motor Skill Learning, Canadian Centre for Behavioural Neuroscience, Department of Psychology and Neuroscience, University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada T1K 3M4, The Journal of Neuroscience, January 21, 2004 • 24(3):628–633

[4] Timothy J. Buschman, Markus Siegel, Jefferson E. Roy, and Earl K. Miller. Neural substrates of cognitive capacity limitations. PNAS July 5, 2011 108 (27) 11252–11255; https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1104666108